McGraw has written an important book, a significant work of narrative non-fiction that everyone who wants to be better-informed about energy policy and national priorities should read. Once you do, you will never again describe natural gas as “clean energy.”

The End of Country (Random House) is exceptionally well-written, readable and entertaining. It describes a new technique for wrenching energy from the earth that may be more devastating than any that has come before: deep drilling, followed by injections of chemical-laden water under pressure to fracture the shale layer of the earth and release natural gas that’s trapped there.

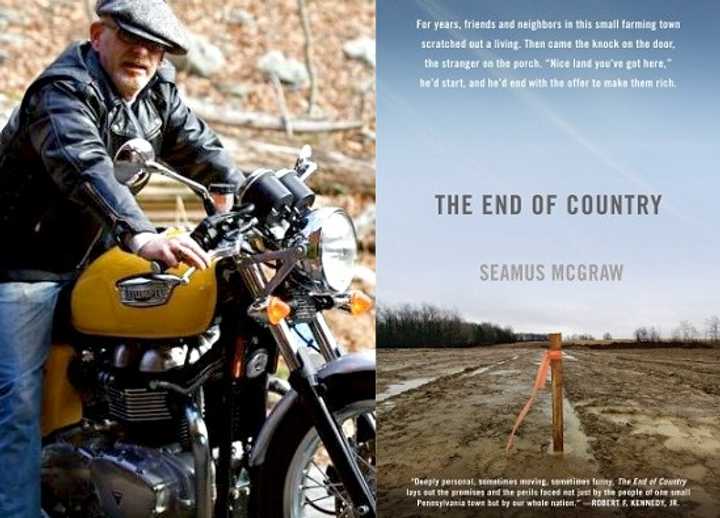

McGraw takes on a huge challenge, but he is up to it. Although originally from the Scranton area — and now of Winona Lakes — McGraw made his name in New Jersey as a wise-cracking, motorcycle-riding reporter who’d sooner go through someone as around them. Trying to duck him wasn’t an option.

In The End of Country, McGraw establishes the geological history and promise of the Marcellus shale region, an area so gas-rich that it alone can provide enough energy to supply the needs of the entire United States for 30 to 50 years. He also describes the actions of the gas companies that descend on rural Pennsylvania, aiming to tap it.

Mary Miraglia

He does this against a backdrop of stories – tales of the people who live there, whose lives will never again be the same.

He does it from the best vantage point possible, that of a working journalist whose own family are members of the small community of Dimock, an epicenter of hydrofracking activity. McGraw’s great-grandfather came from Ireland, only to die in Pennsylvania’s coal mines, where his grandfather also worked.

McGraw’s father — a systems analyst — had different ideas. After moving the family “up country,” he discovers, through lessons large and small, that farming is an extremely difficult life.

His family soon faces the same decision as all of those around them, and eventually comes to the same conclusion, McGraw says: “The gas and the changes it would bring were as inevitable as death.”

The End of Country details the sequence of events that brings a group of people from different backgrounds, circumstances and goals into a fairly cohesive unit that begins to oppose the gas companies – but in an effective way, thanks in large part to the resources of the Internet. The intelligent opposition that developed could not have been possible, in fact, without the information, contacts, and networking that’s online, McGraw says.

And although the story ostensibly centers on Dimock and the people who live there, the events that take place are repeated throughout the state’s rural areas. The farmers, dairymen, quarry owners and retirees who make up most of the population weren’t equipped to deal with the sometimes-devastating effects of gas drilling. It’s crushing for them to discover that the government agencies tasked with monitoring and controlling the human and environmental damage are essentially clueless — and, worse, absent.

Right from the start, there’s an inherent unfairness. The people who sign their leases first, those who tend to have less ability to resist – the poor, the elderly, the hopeless — get the lowest prices. Despite the glaring inequity, they’ve nowhere to turn.

State agencies haven’t established a price floor, they don’t monitor what’s paid – they don’t even provide the landowners with information to help protect themselves against the unexpected and sometimes harmful effects of the drilling: the noise and dirt; the roads cut cruelly across properties; damage to walls, buildings, and wells; toxic spills of frack water — and explosions. Even the death of a beloved dog.

Long-term potential health consequences? These aren’t even mentioned.

Thankfully, the state doesn’t stay ignorant forever. It just takes awhile.

The abuses finally become so overwhelming that the state DEP stops work for the Cabot company, one of the largest and most active not just in Dimock but throughout the entire state. More abuses are revealed, and penalties imposed include the closing of wells.

DEP Secretary John Hanger lays the fault clearly at the feet of the gas company, saying: “Cabot had every opportunity to correct these violations, but failed to do so. Instead, it chose to ignore its responsibility to safeguard the citizens of this community and to protect the natural resources there.”

By the time McGraw’s family gets to deal with the why, how and to whom to lease to, his dad has been dead a decade. The old man’s charge of trust for the land is ever-present in the family’s deliberations. They sign a lease with the gasmen for a fairly decent amount of money.

Then, as the well is being cut into the family farm where he grew up, McGraw traces one of its legs along the path he and a childhood friend often took into the woods — to sneak cigarettes and do other things that boys do:

“I could envision the spot where the leg ended. It had always been a special place to me. It was at that precise spot – right about this time of year, when the leaves were gone and the cattails along the creek had turned brown – that Ralph and I spotted that white deer, an albino, foraging for grass.

“It’s still the only one I’ve ever seen in the wild. I shook off the superstitious Irish urge that lingers in me even now to read anything more into it . . . but . . . I couldn’t help but wonder whether my son would ever have a chance to stumble across so magical a creature while walking through these hills, or whether the magic would be chased away by the din and dirt of industry.”

He wonders “what kind of karmic lessons my father might imagine were now in store for the rest of us.”

The beauty of The End of Country is that McGraw leaves us wondering, too.

Once you’ve read it, you’ll find yourself thinking about more than the utility bill every time you turn up your thermostat.

{loadposition log}

Click here to follow Daily Voice Monsey and receive free news updates.