Federal prosecutors have branded Bernard B. Kerik a crook whose hubris will bury three decades of public service. Yet in the months leading up to his fraud and conspiracy trial in Westchester, beginning next month, I’ve seen Kerik hugged and welcomed warmly by citizens. He’s been saluted by uniformed police officers, hailed by people he helped escape a tumultuous Iraq, and embraced by survivors of 9/11.

A federal appeals court on Oct. 28 uphead a judge’s order out of White Plains that Kerik be held without bail. The lower court judge said Kerik tried to influence potential jurors by giving a defense attorney court-sealed documents from the government’s case against Kerik for allegedly accepting extensive renovations on his Riverdale apartment in exchange for helping a Clifton-based contractor get city work.

What makes the entire episode remarkable for me is the public reaction. “Pay to play” reformers are having a field day. But a massive wave of average Joes sees an American icon being needlessly vilified.

Kerik bristled when I jokingly suggested a story about how, no matter what the government says, chicks still dig him.

“Don’t be writing that garbage,” he said.

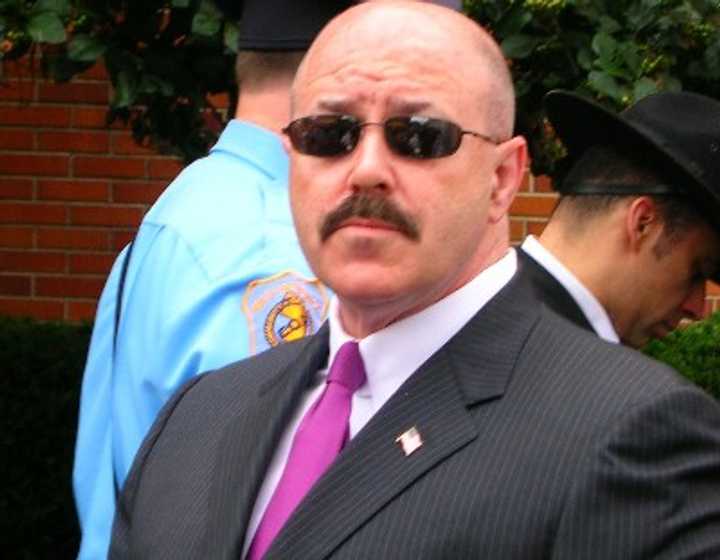

Kerik leaned forward in the desk chair of his home office and gave me that familiar steely look, the one you see in 99 percent of the photographs taken of him since 9/11.

Only this time he wasn’t in a dark pinstriped suit: He was comfortable in a sweatshirt, jeans and sandals, in a downstairs room appointed with countless awards, photos, and other mementos of such a storied career that he could put a turnstile at the front door and have crowds moving through at a brisk clip.

On the front steps with two of his guard dogs

I sat in the boss’s easy chair, exhaling now that his son, Joe, a Newark police officer, had gottten the frisky guard dogs out of the room. Kerik’s closest associate sat with us.

The barrel-chested city kid once annointed “America’s Top Cop” told the story of a woman who approached him while he was in Jordan, saying her husband had taken their daughter to Syria, along with her passport.

“If I can’t find her,” Kerik said she told him, “I’ll never see her again.”

Kerik called his associate, a former prison warden. “You get her to the border,” the former commissioner told his right-hand man. “I’ll get her to Syria.”

His trustworthy associate did his job, as always. Meanwhile, Kerik kept his word.

The woman found her daughter with family members, and the associate brought the two to a basement church to hide. Meanwhile, Kerik exchanged text messages with the woman, assuring her that they were nearly home-free.

He then rang up a contact in the Jordanian government who’d been awaiting his call. The official scooped up both mother and daughter, Kerik said.

The two now live in Washington, D.C.

At JCPO Marc Dinardo’s funeralTheodore Roosevelt once said: “A man who is good enough to shed his blood for his country is good enough to be given a square deal afterwards. More than that no man is entitled, and less than that no man shall have.”

I got that quote from Bernie.

Kerik sat on the edge of his desk, arms folded, as he told another story, this one from Iraq. It began with a Facebook message he got from a woman who said her father and brother threatened to kill her if she didn’t marry the man of their choice.

Kerik had a commando team “snatch them up” and bring them to police headquarters in Baghdad.

“If anything happens to this girl,” he said he told them, “we’re gonna kill you.”

Then he let them go — adding to the myth created when someone dubbed the former Passaic County jail warden “The Sheriff of Baghdad” and another called him the “Baghdad Terminator.”

The woman eventually married the man she loved, an Armenian. They, too, live in the U.S. now.

Sounds a bit like the mob, I told Kerik.

“What are you supposed to do?” he said, shrugging his broad shoulders. “Tell these people you couldn’t be bothered?

“At the end of the day, I don’t care who you are,” Kerik added. “Unless you’re been battle-tested, until you’ve been there, you don’t know how you’re going to act.

“Maybe you just had to be there.”

I keep my opinion of this conversation to myself, not as some repayment for unfettered access. Rather, I have deep personal feelings about the avenger syndrome, and what drives men to believe they can strong-arm their way to “righting” what’s gone wrong.

Through nearly three decades in media, I have also seen how invincible a man can feel when he’s able to make such things happen through sheer defiance.

U.S. District Judge Stephen Robinson warned Kerik that sensitive documents he’d been given for his defense should remain confidential. Next thing you knew, they showed up on a Web site affiliated with his defense.

Like his supporters, Kerik believes he shouldn’t be here in the first place — that he shouldn’t have been forced to spend millions of dollars for lawyers, that his international consulting firm on urban security shouldn’t have been stopped dead in its tracks, that he should be praised for his contributions to America’s security instead of painted as yet another corrupt public servant. It somewhat overlooks the fact that he already has pleaded guilty to similar charges in state court and paid some hefty fines.

A high school dropout born in Paterson 54 years ago, Bernie Kerik believes federal prosecutors have deliberately abused their authority for the sole purpose of trashing his “only-in-America” life story.

“[It’s] disappointing and upsetting that someone can take 30 years of unparalleled service to his country, dedicated service to his country and then place a cloud over it with the appearance that everything you’ve ever done is wrong.”

And then, in a very telling statement, he said: “The prosecutor in this case brought the charges because of who I am.”

That Kerik would defy a consent order by posting confidential material surprised me. I believed him when he said he believed a day of reckoning would come, just as it did earlier this year for prosecutors in the Ted Stevens case.

Attorney General Eric Holder, who terminated the Stevens prosecution, has told U.S. attorneys that their job “is not to win cases. Your job is to do justice.”

But “doing justice” can be quite subjective.

Robinson already has tossed out wire-fraud charges, citing the statute of limitations, in a wide-ranging federal indictment that he dubbed a “laundry list” of allegations. The judge also separated the tax-fraud charges into a separate trial from the one beginning this week.

Robinson also dismissed allegations that Kerik lied to the White House when he denied having any secrets that could embarrass him or then-President Bush in 2002.

I exchanged emails with one of the women Kerik told me about. She praised him but was afraid to say much more, lest she be discovered — a reaction that reminded me of the way many of Bernie’s so-called friends have acted this past year.

He’d never admit it, but the stocky tough guy from the streets feels the sting of public rejection by those he believed would rally to his defense.

Recently, a group of judges who were gathered in a private room at a North Jersey restaurant invited him up after they heard he was in the dining room. Although he presents the anecdote with a positive spin, his eyes betray disappointment. Some of them barely acknowledged him in public.

Yet he remains the stand-up guy. In fact, Rudy Giuliani’s former driver, bodyguard, police commissioner and onetime business partner is still willing to take a bullet for his old boss.

“I haven’t spoken to [Giuliani] in a long time. It’s pretty much by agreement,” Kerik said. “I don’t want him involved in this process [the trial]. I don’t want rumor and innuendo and allegation affecting him.”

I’d have believed him, too, if he’d only looked me in the eye once during that comment.

It’s when he’s moving through gatherings of uniformed officers — the excitement rising so palpably that you feel they’re about to lift him on their shoulders — that Bernie Kerik beams.

Unless you come from hardscrabble beginnings, it’s difficult to understand just how important such affirmation is.

Raised by an abusive adoptive dad, Kerik later learned his mother had been a prostitute who was tortured and killed when he was 14. Four years later, already a black belt, he joined the military police during the Viet Nam war.

While correction commissioner, he reduced violence at Rikers Island; as police commissioner, he merged all intelligence, so that homicide detectives and burglary investigators, for instance, could work together to solve crimes; as a private citizen, he was floored by President Bush’s offer to go to Iraq to shore up its police force.

But these milestones, along with his stint as warden of the Passaic County Jail, remain the solid lines in the public sketch of Bernie Kerik.

In the shaded areas are his creation of the Office of Psychological Warfare, along with brigadier general Robert A. McClure, and his subsequent work as an instructor to U.S. troops. There also were a few years spent as a private guard to Saudi Arabian King Saud Abd al-Aziz.

Until Robinson revoked his bail last week, the man who considers Oliver North a hero had been moving in and out of the shadows again.

One day he’d attend a police funeral, the next he’d dropped in on an ordinary citizen who expressed an interest in meeting him. He kept extremely late hours, sleeping little, as he wrote and posted opinion pieces on national defense on his web site. Now and then, he discussed those views on Geraldo Rivera’s cable show.

Kerik continued to dine at the Brownstone in Paterson — once considered among the state’s finest restaurants, now better known as the joint owned by the husband of one of the “Real Housewives of New Jersey.”

He even did a cameo on the show with his dogs, play-acting as their trainer.

During our first meeting, Kerik softened as he showed me crayon drawings his kids gave him for a children’s book that explains what happened on 9/11 — “but in a way that doesn’t frighten them.”

Yes, Bernie Kerik was writing a children’s book. It tells the true story of an American flag found at Ground Zero that went to the moon.

Someone from his department left the flag on the commissioner’s desk in the wake of the attacks, with a note attached. Old Glory was so smoky, he said, “the whole office smelled.”

An officer personally delivered the charred flag to NASA, stopping along the way at a hotel in Washington, D.C., where he rented a suite with separate beds — so that the flag could rest on the one next to him.

Kerik smiled as he recalled how the flag made its way into space, how it showed the resiliency of the American people — but also how it displayed a defiance against anyone who would dare mess with the big dog.

In his own complex way, “BK” left me wondering: Is this a metaphor that requires explanation?

Or is this:

One day this summer, Kerik took his daughter to the mall, where she noticed a tattered American flag flapping in the breeze over a sporting goods store. They went inside, where Kerik tried in vain to get someone to pull it down. Even the store manager said he didn’t have the authority.

“I should’ve just climbed up there and gotten it myself,” Kerik said, angrily. “But my daughter was with me. I had to hold my tongue.”

As soon as he got home, Kerik immediately e-mailed the president of the company. Within hours, he had a response.

The flag had been replaced.

ALL PHOTOS BY CLIFFVIEWPILOT.COM. NO USE WITHOUT PERMISSION.

Click here to follow Daily Voice Paterson and receive free news updates.