Authorities had no corroborating evidence in the 1989 beating and rape. The “confessions” given by those taken into custody were at odds with one another. Still, all five were found guilty of the crime.

Ten years ago, notorious serial rapist Matias Reyes gave authorities intricate details of the attack — he even drew them a map. His DNA matched that found in vaginal swabs.

With support from the Manhattan DA’s office, the convictions of the five original defendants were vacated.

New York State has a “corroboration rule.” It requires that “[a] person may not be convicted of any offense solely upon evidence of a confession or admission made by him without additional proof that the offense charged has been committed.”

Jerry DeMarco Publisher/Editor

In the Central Park jogger case, there was the victim and the condition in which she was found.

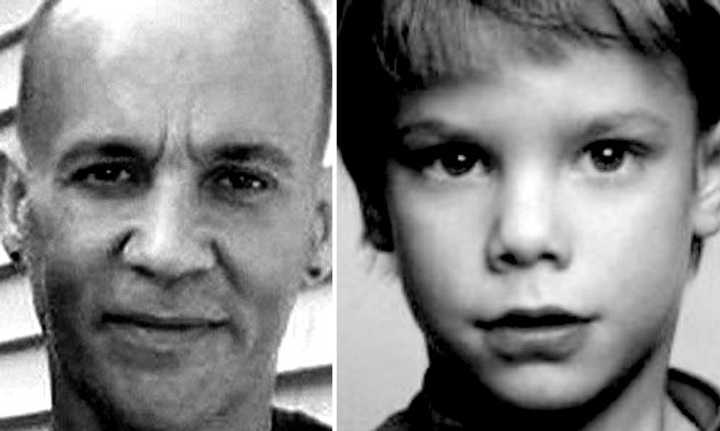

In the Etan Patz case, there’s no proof of anything other than the boy’s disappearance — 33 years ago yesterday.

We don’t know if he was spirited off somewhere and killed, or died, years later. We don’t know whether some bizarre circumstances exist under which he would still be alive (See: Jaycee Dugard).

Reports are that 51-year-old Pedro Hernandez — a builder with no previous criminal record — broke down and cried when he confessed.

NYPD Commissioner Ray Kelly says Hernandez also told loved ones more than 30 years ago that he’d “done a bad thing and killed a child in New York.”

Authorities haven’t yet offered a possible motive why a teenaged stock clerk at a Manhattan grocery near the 6-year-old’s apartment would lure him into the store, strangle him in the basement and dump his body in the trash down the block (If it’s sexual, they may be trying to spare Stan and Julie Patz).

Back then, finding evidence of a body in a New York landfill even a week later was all but impossible.

So the question becomes: If no other specific, corroborative evidence emerges, will a judge allow prosecutors to try Hernandez based solely on the confession?

Or spinning it even further out: Would a judge sign off on a plea bargain?

My guess is there’s some “smoking gun” evidence the NYPD hasn’t revealed.

In this day and age, the highest-profile police department in the United States, if not the world, wouldn’t bring a case this monumental without cause. Given all the criticism Kelly has withstood the past year or so, it’s unfathomable that he’d allow it.

Although volumes of scholarly work have found that false confessions are the leading cause of wrongful convictions, advances in DNA processing have sharply decreased those numbers — and freed wrongfully some convicted people.

What’s more, as a society, we’ve come to realize that people confess to crimes they didn’t commit without coercion, contrary to what might be considered common sense (If you had a nickel for everyone who confessed to kidnapping the Lindbergh baby, you’d have lots of nickels).

The U.S. Supreme Court recognized it, too, stating that “a confession is like no other evidence,” is “uniquely potent” and is “profoundly prejudicial.” The high court ruled that legal safeguards must be in place, beginning with “trustworthiness.”

Before a judge finds a confession trustworthy and allows it to be entered as evidence, the Supremes said, the accused must:

• provide information that leads to the discovery of evidence that authorities didn’t have before — something that belonged to Patz, for instance;

• know of highly unusual elements of the crime that weren’t publicized — which could be difficult in the Patz case. Investigators do this precisely to weed out the wackos; it’s called “holdback evidence.” But without a body or crime scene, what could only they and the supposed killer know?;

• have specific details, not the average type that could apply to any crime — for instance, a mole or other distinguishing mark on the boy.

Judges today also get to view videotaped confessions, which allow them to assess the tone and tenor of an interrogation, to be sure the accused wasn’t unfairly coerced or intimidated.

Then again, these tests can’t be weighed against detectives, whose sworn duty is to solve crimes. The State deserves as much fairness as any defendant.

Hernandez could be telling the truth. Who knows? After all, he was one of the original suspects after Etan Patz disappeared.

Here’s the kicker: Judges still allow confessions more often than not. They’ve even done it when DNA evidence proved otherwise.

It happened not too long ago, in fact — in the case of the Central Park jogger.

{loadposition log}

Click here to follow Daily Voice Teaneck and receive free news updates.