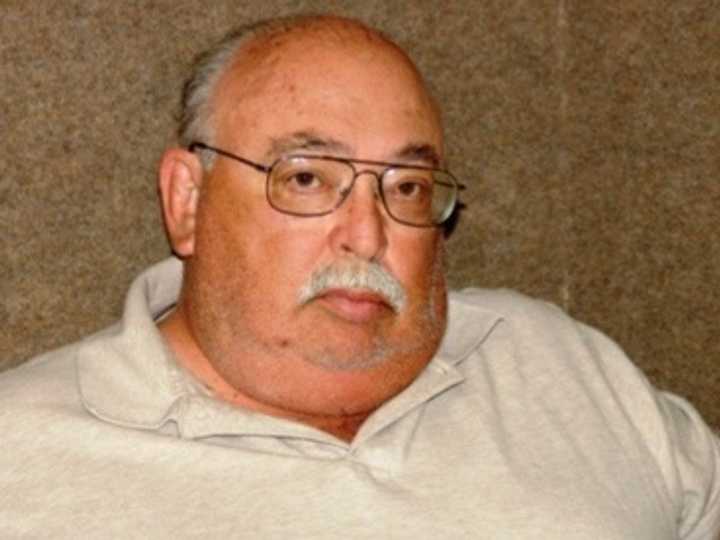

Edward Ates

One of Bergen County Prosecutor John L. Molineli’s investigators was doing something else when the more-than-five-minute call between Edward Ates and his lawyer was picked up and inadvertently recorded on the wiretap, the decision says.

Investigators cannot listen in on such calls – a legal prohibition issued by the judge in the case and clearly posted in the wire room.

Ates was later convicted of what the sentencing judge called the “cold and calculated execution” of 40-year-old pharmaceutical executive Paul Duncsak in his home with a .22-caliber handgun, despite the unique defense argument that Ates was “too fat” to carry it out. He is serving a lifetime prison sentence.

The officer monitoring calls at the time testified that he was working on the log of intercepts and didn’t hear or see signals when the call between Ates and defense attorney Walter Lesnevich was picked up at 3:25 p.m. Oct. 23, court records show.

The officer – who was working his first wiretap — said he likely didn’t hear the audio signal because he’d put down his earphones, which were plugged into the equipment. As a result, the appeals judges said, he was unaware that the entirely of the five-minute call was recorded.

Reviewing calls at the end of his shift, the officer realized what had happened. He immediately notified a sergeant, who “instructed him that the call was not to be listened to,” the judges wrote.

Everyone involved testified that they didn’t listen to the call, either. That includes the assistant prosecutor who originally handled the case, John Santulli.

The call wasn’t played for the grand jury that indicted Ates, nor was it given to Assistant Prosecutor Wayne Mello, who later took over the prosecution.

What angered the higher court was that the matter ended there.

Santulli, who no longer works for the agency, testified “that when alerted to this event, which he characterized as unusual, he did not seek out his supervisor or the Bergen County Prosecutor, nor did he advise the issuing judge, Judge [Marilyn C.] Clark,” the appeals decision says.

“Although the recorded conversation was provided to defense counsel as part of the voluminous discovery,” it says, “there was no specific mention made of call #278 having been intercepted.”

Bergen County Prosecutor’s detectives later arrested Ates on charges of murder and other crimes, including burglary and weapons possession.

An indictment was returned on Sept. 28, 2007.

Lesniak wrote to Superior Court Judge Peter Doyne in Hackensack in January 2009, claiming that the detectives illegally intercepted and taped conversations he had with Ates. During the particular call in question, he said, he and Ates discussed the “vital strategy [they] planned to use at trial.”

Members of the prosecutor’s office involved in the case “built a wall around their misconduct and … never disclosed that they recorded this conversation,” Lesniak argued.

During a conference with Doyne, Molinelli admitted that his office intercepted and recorded the particular conversation. But he maintained that no one listened to it and that it wasn’t in any way used in the investigation or presented to the grand jury.

The appeals judges agreed that the phone call be suppressed, along with 23 subsequent recorded conversations that Molinelli said also were “minimized” – meaning the audio was immediately turned off, leaving nothing but dead air.

“Judge Clark’s orders … were violated,” along with the New Jersey Wiretap Act, the Appellate Division wrote. “[T]he State’s failure to bring it to the attention of, and to seek directions from, the wiretap judge, was knowing and intentional. [I]t had an obligation to bring it to Judge Clark’s attention. It did not do so.

“Based upon the State’s unauthorized and unlawful interception, and the conduct which followed thereafter, which this court determines to be equally or even more egregious …. the integrity of the wiretap operation became impugned,” the appeals judges wrote.

However, the higher court let stand the indictment that led to Ates’s trial and refused his request that the entire case be thrown out.

It noted that the recording was an inadvertent “isolated and aberrant event” and that the monitoring officer involved “was forthright and candid in admitting that by leaving the earphones in the monitoring device he thereby improperly recorded and failed to minimize a privileged communication.” They said he also “accepted responsibility for his error,” reporting it to his supervisor at the end of his shift.

The judges said they also found no proof that anyone in the prosecutor’s office listened to the recording.

That said, they deemed “various aspects” of the prosecutor’s office’s response to the gaffe “troubling.”

Although members of the monitoring team were told not to listen to the recording, “no similar written admonition appears to have been prepared,” the judges wrote. “Neither was any more detailed narrative report prepared relative to the incident beyond the wiretap log synopsis as requested by the assistant prosecutor.”

What’s more, they added, “[r]ather than immediately advising Judge Clark that her orders had been violated and that potentially privileged communications had been intercepted and fully recorded and seeking further direction from Judge Clark, the State opted to remain silent.

“At a minimum, Judge Clark could have ordered the recording sealed, so that further potential intrusion into the sanctity of that privileged communication could have been prevented. In addition to sealing the recording, certain other options may have been available to Judge Clark at that juncture, including terminating the wiretap operation, refusing to enter any further wiretap orders or extensions, or referring the matter to the Attorney General’s Office or another appropriate agency for investigation and/or prosecution of the case against defendant.

“However, we will never know which of these or any options Judge Clark would have implemented due to the State’s failure to bring the violation to her attention despite the State’s awareness of it.”

The evidence against Ates was “voluminous, consisting of some eighty compact discs,” the appeals panel added. “Rather than apprising defense counsel of this improper interception at the time discovery was provided, the State again chose to remain silent, thus placing defense counsel in the position of having to forage through this voluminous discovery until eventually coming upon it.”

(NOTE: The Appellate Division also rejected Ates’s argument that the prosecutors needed a warrant from a judge in Florida to run a wiretap on calls from his home state when they took up this case.)

{loadposition log}

Click here to follow Daily Voice Hackensack and receive free news updates.